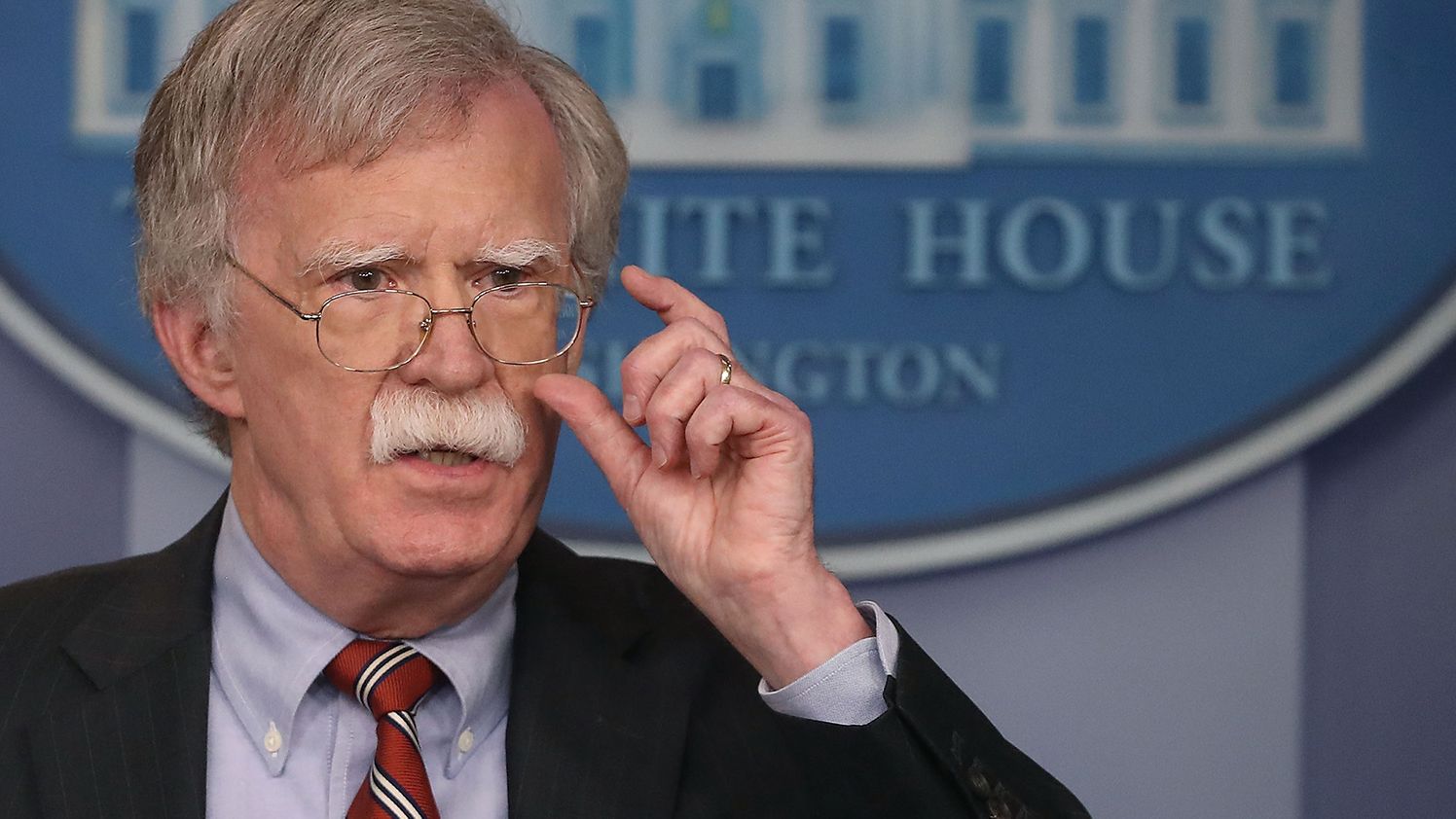

It’s become almost cliché to say Donald Trump sees the world through a transactional lens, but former National Security Advisor John Bolton forces us to confront what that really means — and why it’s so dangerous.

In a recent interview, Bolton lays bare a truth that’s easy to overlook amid the daily noise of campaign rallies and culture war skirmishes: Trump doesn’t approach foreign policy as a statesman. He approaches it as a man negotiating for himself, not for his country.

He doesn’t see Vladimir Putin as a threat, Bolton argues, because Trump doesn’t really see geopolitical threats at all. What he sees are personalities — people he likes, people who flatter him, and people who make deals. If he has a good relationship with the “head of a foreign government,” then, in his mind, America has a good relationship with that country. That’s it. That’s the metric.

It’s a deeply solipsistic worldview, and it has terrifying implications.

To Trump, diplomacy is a stage for personal affirmation, not a means of navigating national security or defending democratic values. Ukraine’s war for survival becomes, in his eyes, “senseless” — not because he sees moral equivalence between Ukraine and Russia (though that’s troubling in its own right), but because he cannot grasp why people would fight for something abstract like freedom, when they could just “make a deal.”

The problem, as Bolton makes clear, is not that Trump has bad ideas about global order. It’s that he has no framework at all. No understanding of alliances, deterrence, spheres of influence — or even the basic mechanics of power projection. He’s not uninterested in these things; he’s simply untouched by them. They don’t fit into the world as he understands it.

And yet, he remains the dominant force in one of the world’s two major political parties. That disconnect between Trump’s personalized foreign policy and the demands of a dangerous, multipolar world should be a five-alarm fire for anyone who cares about America’s global role — or its long-term safety.

Bolton, hardly a dove, reminds us that strategic competition doesn’t pause just because we’re tired of it. China and Russia are not neatly separable threats. Neither are Iran and North Korea. The post-Cold War idea that the world would flatten into a marketplace has collapsed, and something much darker has emerged in its place — an axis of regimes who, though not always ideologically aligned, share a common interest in undermining the West.

Trump, instead of recognizing that, continues to bluster about trade deficits and being “respected” by strongmen.

What’s worse, Bolton suspects there’s no internal trigger that could change Trump’s mind. “He can receive good advice,” he says, “but it doesn’t take.” The only external force that might shake some of Trump’s base, Bolton muses, is economic pain — say, from tariffs that quietly raise prices for the very working-class voters Trump claims to champion.

That is, of course, cold comfort.

In the meantime, the Republican Party — or what’s left of its Reaganite core — remains mostly silent. Bolton says many on Capitol Hill privately disagree with Trump’s approach, but publicly fall in line, terrified of being “primaried” by a Trump-endorsed challenger. So the party that once preached “peace through strength” is now reduced to flattery-as-policy, with NATO leaders reportedly fawning over Trump just to keep him from blowing up the alliance.

And yet, Bolton isn’t entirely without hope. He believes the illusion of Trump’s diplomacy — the myth that he alone can “make the deal” — is unraveling. His promises on Ukraine fell flat. Putin didn’t fold. The war drags on, and Trump is already retreating from even trying to end it.

But the most sobering takeaway from Bolton’s remarks isn’t about Ukraine or NATO or even Putin.

It’s about us.

What does it say about a nation when its leader doesn’t think in terms of right and wrong, peace and war, allies and enemies — but only in terms of himself? What happens to a country when the presidency becomes a mirror, rather than a window?

We used to understand that leadership involved more than gut instinct and grievance. That global stability required sacrifice, consistency, and yes — boring things like strategy. But strategy requires a worldview. And in Trump’s case, there may be none to speak of.

Just deals. And when the deal goes bad, he walks away.