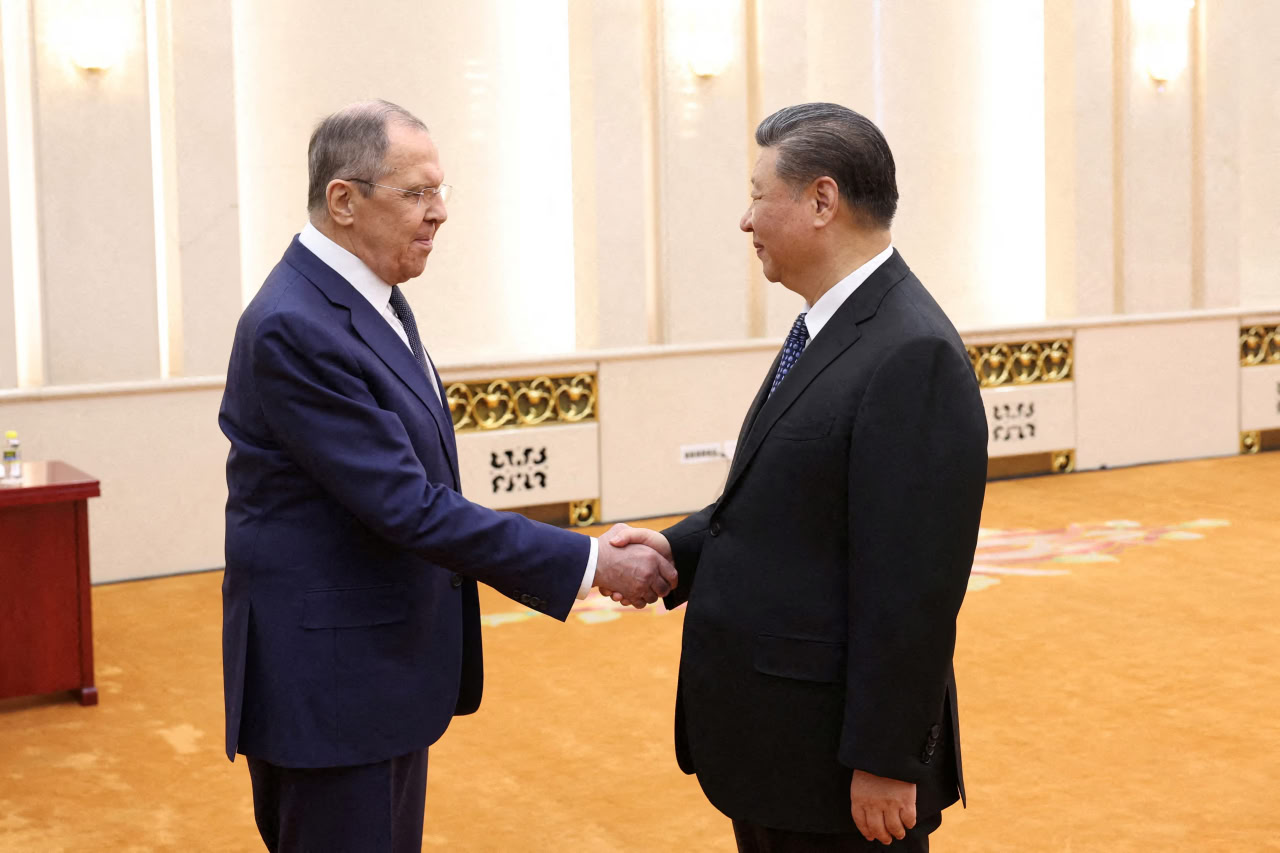

In the grand chessboard of global politics, Vladimir Putin has long dreamed of a multipolar world where Russia stands tall as a counterweight to Western dominance. Yet, as Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov shakes hands with Chinese leaders at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, you get the sense that Russia’s ambitions are crumbling under the weight of its own missteps. Far from achieving parity with Beijing, Moscow is slipping into the role of a junior partner, a vassal state tethered to China’s rising star. The SCO, billed as an “Asian NATO,” is less a partnership of equals and more a stage for China’s quiet but ruthless domination—a dynamic that reveals not just Russia’s declining influence but the stark reality of its strategic isolation.

The SCO, founded in 2001 by China, Russia, and several Central Asian states, was meant to embody a shared vision of countering Western hegemony. On paper, it’s a coalition of 10 nations—including heavyweights like India, Pakistan, and Iran—committed to mutual security and economic cooperation. In practice, it’s a Chinese-orchestrated mirage. Beijing pays lip service to multilateralism, but the organization serves as a tool to cement its regional dominance while sidelining Russia. You can almost feel the tension behind the diplomatic smiles: China’s President Xi Jinping offers warm platitudes, but his country’s actions tell a different story. From stealing Russia’s hypersonic technology to securing energy dominance in Central Asia, China is playing a long game that leaves Moscow scrambling to keep up.

What’s troubling is how starkly this dynamic exposes Russia’s vulnerabilities. Putin’s fixation on battlefield victories in Ukraine and evading Western sanctions has left Russia myopic, unable to match China’s forward-thinking strategy. Beijing isn’t just outpacing Moscow; it’s draining it. Chinese firms are snapping up Central Asian resources—mines, factories, and infrastructure—while Russia clings to fading political influence. The Belt and Road Initiative, China’s sprawling infrastructure project, is a case in point. In countries like Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, China builds roads and railways, only to saddle these nations with crippling debt. It’s not conquest in the traditional sense but a subtler form of control—call it debt colonialism—that ensures Beijing’s grip on the region’s economic future. Russia, once the dominant power in Central Asia, can only watch as its former Soviet satellites drift into China’s orbit.

The historical backdrop makes this shift all the more poignant. The Sino-Soviet split of the 1950s and 1960s, when Mao Zedong rejected Soviet leadership, set the stage for decades of mistrust. In 1969, tensions boiled over into a near-nuclear confrontation on Damansky Island, where Chinese and Soviet troops clashed. That history lingers, a ghost in the room during every SCO meeting. China’s leaders haven’t forgotten the Soviet era, when figures like Nikita Khrushchev dismissed Mao as a mere peasant. Today, Beijing views Russia not as an equal but as a resource-rich carcass to be picked clean. As historian Sarah Paine, a scholar of Chinese-Russian relations, has noted, the question isn’t if China will turn on Russia, but when. It’s a sobering reminder that alliances built on expediency rarely endure.

Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s longest-serving foreign minister, embodies this fading relevance. A polished diplomat fluent in English, French, and even the languages of the Maldives and Sri Lanka, Lavrov is a relic of Soviet sophistication. He’s the kind of figure who could charm a room while deflecting accusations of war crimes. Yet, for all his finesse, Lavrov is a man without real power. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, he was reportedly informed mere hours before—a humiliating sidelining for a foreign minister. In Beijing, his presence is little more than a formality. China knows Putin’s inner circle calls the shots, and Lavrov’s diplomatic overtures are just theater. You can’t help but feel a twinge of pity for him, a man tasked with selling a partnership that Beijing has no intention of honoring.

China’s opportunism is most evident in its exploitation of Russia’s technological and military assets. Joint projects on hypersonic weapons, drones, and air defense systems sound cooperative, but they’re riddled with betrayal. Take Russia’s Zircon hypersonic program, for instance. Hacked in recent years, likely by North Korean operatives acting on Beijing’s behalf, the program’s secrets are now in Chinese hands. The FSB, Russia’s intelligence service, has quietly classified China as a top-tier espionage threat—a stunning admission for a supposed ally. Even in space, where Russia once held sway, China is sidelining Moscow. A joint lunar base project by 2035 sounds promising, but Russia’s role is reduced to supplying nuclear energy, while China controls the science, budget, and decision-making. It’s less a partnership than a transaction, with Russia playing the role of a glorified fuel station.

Central Asia, once Russia’s backyard, is another arena where China’s ascendancy is undeniable. Countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, wary of both fading Russian influence and China’s economic stranglehold, are caught in a geopolitical bind. They attend SCO summits not out of loyalty but necessity, hedging their bets in a region where options are scarce. China’s Belt and Road projects have poured billions into infrastructure, but the price is steep. Local governments, unable to repay loans, cede control of land and resources, effectively handing Beijing the keys to their economies. Russia, meanwhile, offers little beyond political posturing. Its inability to compete economically underscores a painful truth: Putin’s Russia has squandered its wealth and influence, leaving it with nothing to offer but raw materials and outdated bravado.

The broader implications are stark. Russia’s so-called allies—China, North Korea, Iran—are partners of convenience, not conviction. North Korea sells artillery to Russia not out of camaraderie but desperation for cash. India, another SCO member, bypasses Russia to buy discounted oil from Iran, undercutting Moscow’s economic leverage. If the United States were to tighten sanctions, forcing China or India to choose between Russia and the West, the decision would be obvious. Russia, isolated and economically hobbled, has little to offer compared to the West’s vast markets and technological prowess. It’s a grim reality for Putin, whose 25-year rule has left Russia not as a global power but as a resource depot for more ambitious players.

What’s most striking is how this dynamic reflects Putin’s broader failure. For decades, he’s plundered Russia’s wealth, prioritizing personal enrichment and military adventurism over long-term development. The result is a country that’s broken—economically stagnant, diplomatically isolated, and technologically outpaced. China, by contrast, plays the long game, leveraging its economic might and strategic patience to reshape Asia’s geopolitical landscape. The SCO, far from being a multipolar triumph, is a testament to China’s ability to exploit Russia’s weaknesses while projecting an image of unity.

Looking ahead, the question isn’t whether Russia will be left behind—it’s how far it will fall. China’s rise is inevitable, but its partnership with Russia is not. Beijing will extract what it needs—resources, technology, influence—and move on. For Putin, the dream of a multipolar world has become a nightmare of dependency. The SCO summit, with its handshakes and hollow promises, is a microcosm of this reality: a stage where Russia plays the supporting role in China’s ascent. As the world watches, you can’t help but wonder: how long can Moscow cling to the illusion of relevance before it’s cast aside entirely?