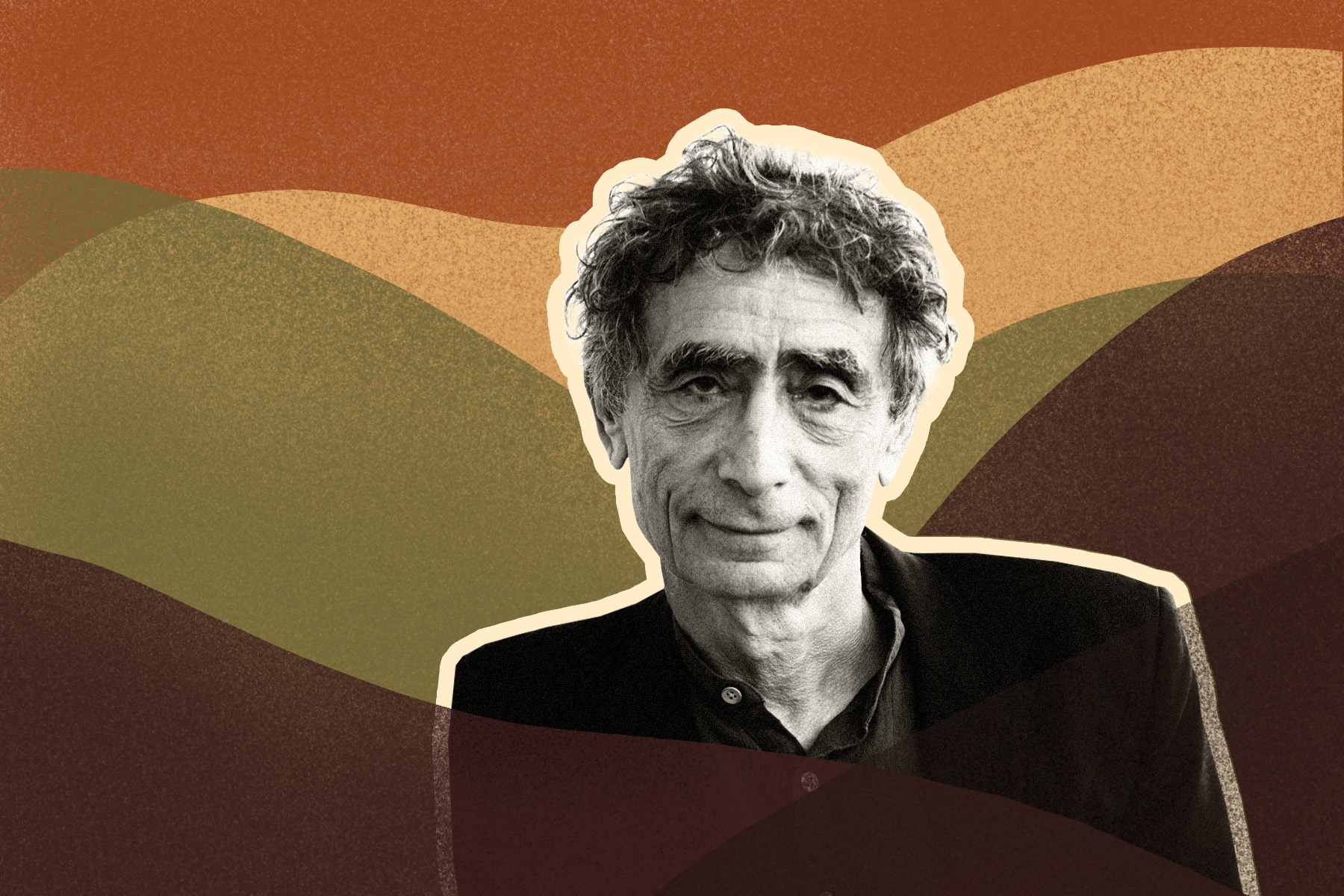

In a world where addiction is often reduced to moral failings or genetic curses, what if the real culprit is something far more human: unhealed pain? That’s the provocative question at the heart of a compelling conversation between addiction expert Dr. Gabor Maté and entrepreneur Joe Polish at a business conference in 2018. Maté, a Hungarian-born physician who survived the Holocaust and later dedicated his career to understanding addiction, didn’t just share statistics—he dismantled myths and urged us to look deeper. With opioid overdoses claiming lives equivalent to a 9/11 attack every three weeks in the U.S., according to the President’s Commission on the Opioid Crisis, Maté’s message couldn’t be timelier. But as we’ll explore, this isn’t just about drugs; it’s about the emotional voids that drive behaviors from workaholism to compulsive shopping, and why society keeps getting it wrong.

Maté’s insights, drawn from decades treating addicts in Vancouver’s gritty Downtown Eastside—North America’s densest hub of drug use—challenge the status quo. Historically, addiction has been viewed through narrow lenses: ancient societies saw it as demonic possession, the 19th century labeled it a vice to be punished, and modern medicine often calls it a brain disease. Yet Maté flips the script, arguing that addiction stems from trauma, a concept rooted in post-World War II psychology when Holocaust survivors like himself began revealing how early suffering wires the brain for escape. In today’s geopolitically fractured world, where conflicts displace millions and economic pressures fracture families, this trauma-addiction link feels eerily relevant. Think of indigenous communities in Canada and the U.S., ravaged by centuries of colonization—residential schools that stripped children of culture and inflicted abuse—leading to sky-high addiction rates. Maté points out that these groups had access to substances like tobacco and peyote long before European arrival, but used them ceremonially for connection, not escape. It was the trauma of genocide and cultural erasure that turned them addictive.

Redefining Addiction Beyond Substances

Maté starts simple: addiction isn’t just about heroin or cocaine—it’s any behavior that offers temporary relief but leads to long-term harm you can’t quit. “It could be gambling, sex, relationships, the internet, Facebook, shopping, eating, or work,” he explains, his voice carrying the weight of personal experience. As a family physician turned addiction specialist, Maté confesses his own battles: a compulsive drive to work that stemmed from childhood rejection, and a shopping habit for classical CDs that masked deeper voids. Why do we crave these escapes? Audience members at the conference chimed in: relief from pain, control, love, escape from anxiety or loneliness. Maté nods—it’s not the addiction that’s the problem; it’s the pain it’s trying to solve.

This resonates in our hyper-connected yet isolating era. With social media amplifying loneliness—studies from the American Psychological Association show rising anxiety among teens—behaviors like endless scrolling become modern crutches. Maté’s take? These aren’t choices; they’re survival mechanisms. He critiques the dominant models: the legal one that punishes addicts as criminals, and the medical one that labels it an inherited disease. Neither addresses the root—emotional pain from life’s hardships. “Addictions begin in pain and end in pain,” he quotes spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle, a reminder that without healing the source, the cycle spins on.

Polish, the host, shares his raw story: molested as a child after losing his mother at four, he spiraled into drugs from pot to cocaine and crystal meth between ages 16 and 18. Later, a sexual addiction wired from that abuse haunted him, even as he built a successful business. Joining a support group for high-profile individuals—billionaires, athletes, politicians—he saw the universality: “That which is most private is most public.” It’s a poignant reflection on how trauma hides in plain sight, affecting even the powerful. Maté connects the dots: Polish’s abuse taught him sex was transactional, not intimate, a compensation for feeling unwanted. Similarly, Maté’s infancy under Nazi occupation in 1944 Budapest left him with a mother’s terror he internalized as rejection, fueling his workaholism as a doctor seeking constant validation.

The Trauma Connection: From Childhood to Society

Diving deeper, Maté unpacks trauma’s role, distinguishing overt horrors—like abuse or war—from “developmental trauma,” where essential needs go unmet. He recounts his own: as a Jewish infant in Nazi-occupied Hungary, he absorbed his mother’s fear, leading to lifelong issues like ADHD, which he sees not as a genetic flaw but an adaptation to stress. “The brain tunes out to protect from distress,” he says. Why the surge in ADHD diagnoses—tripling in U.S. kids from 2002 to 2013? Stressed parenting environments, he argues, amid economic pressures that leave parents overworked and emotionally distant.

This extends to broader societal wounds. Indigenous addiction epidemics, Maté notes, exploded post-colonization: in Canada, residential schools abused children as late as the 1960s, with one woman he knows punished at four by having needles stuck in her tongue for speaking her native language. Geopolitically, this mirrors global traumas—from Syrian refugees fleeing war to American inner cities gripped by poverty—fueling addiction waves. The opioid crisis, hitting white middle-class communities now, has lowered life expectancy for the first time in decades, per CDC data. But as Maté observes, it’s been devastating Native reservations for generations, ignored until it affects “us.”

Even “respectable” addictions like power or profit wreak havoc. Maté hesitates but calls out business leaders chasing endless wealth to fill inner holes, contributing to environmental crises. He references Napoleon, a genius addicted to power whose wars killed millions—a historical echo of today’s leaders shaped by unaddressed pain. Reflecting on U.S. politics, Maté analyzes figures like Donald Trump (raised by a domineering father) and Hillary Clinton (taught to suppress vulnerability as a child), showing how trauma manifests in grandiosity or stoicism, influencing global decisions.

Healing: Compassion Over Punishment

So, how do we interact with addicts causing chaos—lying, stealing, self-destructing? Maté advises families: choose rationally. Either leave if the pain is too much, or stay with understanding, supporting without judgment. The irrational path? Trying to force change through coercion. “You can’t punish pain out of people,” he insists, critiquing the U.S. prison system as a perfect machine for entrenching addiction through stress and isolation.

Treatment? Start with compassion: ask what the behavior provides, trace it to trauma. Maté laments medical training’s trauma-phobia—his colleague, Detroit ER doctor Jamie Hope, received zero lectures on brain-environment interactions in med school. Programs like AA help but often skirt core wounds. Epigenetics adds nuance: trauma alters gene expression across generations, but neuroplasticity offers hope—the brain can rewire with recovery, reclaiming the lost self.

For victims of abuse, like Polish confronting his perpetrator, Maté urges: honor your anger if unhealed, but as recovery deepens, compassion may emerge, recognizing the abuser’s own trauma. It’s a cycle-breaking insight, especially in #MeToo’s wake, where figures like Harvey Weinstein embody predatory addictions rooted in pain.

A Call for Change in a Hurting World

Maté’s message is a wake-up call: addiction is human, born from pain we all risk. In a conference of entrepreneurs, it sparked revelations—Polish notes how even brief mentions drew floods of personal stories, proving its relevance. As global tensions rise, from climate displacement to economic inequality, ignoring trauma’s role in addiction courts disaster.

What if we shifted? Decriminalize substances logically—heroin addicts fare better health-wise than heavy smokers or drinkers, Maté argues, citing medical facts. Invest in trauma-informed care, support families, and foster environments where kids feel safe. It’s not easy, but as Maté’s life shows—from Holocaust survivor to healer—recovery is possible. His books, like “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts,” and website (drgabormate.com) offer starting points.

In the end, isn’t this about reclaiming our humanity? By seeing addiction through pain’s lens, we might just heal not only individuals but societies fractured by unseen wounds. As Polish aims with initiatives like Genius Recovery, it’s time for influential voices to lead the charge—before another 9/11’s worth of lives slip away.

This post really opens the door to thinking about addiction in more nuanced terms—especially how behaviors like workaholism might share roots with substance use. It makes you wonder how many people are silently struggling under the radar.

I appreciate the broader definition of addiction here—seeing things like workaholism through the same lens as drug use is uncomfortable, but necessary. It really underscores how pain can manifest in ways we often ignore or even reward.